Hash, displace, and compress: Perfect hashing with Java

This article explains a straightforward approach for generating Perfect Hash Functions, and using them in tandem with a

Map<K,V>implementation calledReadOnlyMap<K,V>. It assumes the reader is already familiar with the concepts like hash functions and hash tables. If you want to refresh your knowledge on the two mentioned topics, I recommend you to read some of my previous articles: Implementing Hash Tables in C and A tale of Java Hash Tables.

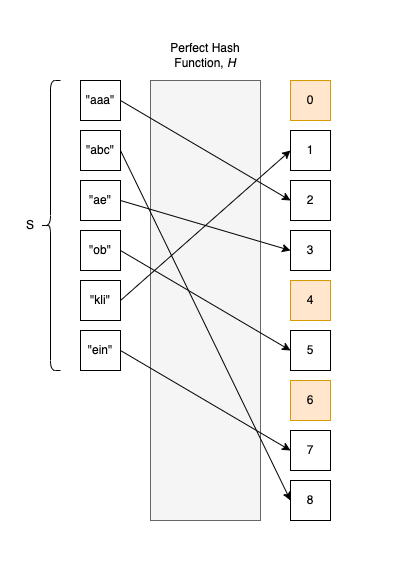

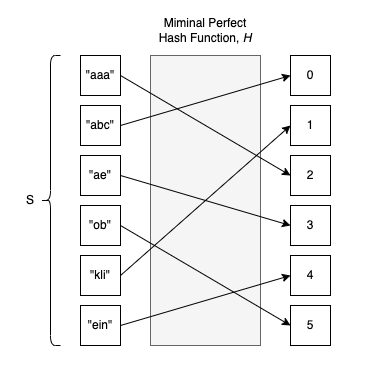

A Perfect Hash Function (PHF), \(H\) is a hash function that maps distinct elements from a set \(S\) to a range of integer values \([0,1,....]\), so that there are no collisions. In other words, \(H\) is injective. This means that for any \(x_{1}, x{2} \in U\), if \(H(x_{1})=H(x{2})\) we can say for sure \(x_{1}=x_{2}\). The contrapositive argument is also true, if \(H(x_{1}) \neq H(x_{2})\), then for sure \(x_{1} \neq x_{2}\).

Moreover, a Minimal Perfect Hash Function (MPHF) is a PHF \(H\) defined on a finite set \(S = \{a_0, a_1, ..., a_{m-1}\}\) with values in range of integers values \(\{0, 1, ..., m-1\}\) of size \(m\).

A function like this would be fantastic to use in the context of Hash Tables, wouldn’t it be so !?

In theory, without collisions, every element goes straight into an empty bucket without risking finding an intruder already settled. Or, in the case of Open Addressing Hash Tables, the element doesn’t have to probe the buckets to find its place in the Universe.

Another (significant) advantage of using an MPHF is the space consideration: we can don’t have to impose a load factor on the Hash Table, because we know there’s a perfect association (1:1) between elements and buckets. When using an MPHF, the load factor is 1.0, compared to ~ 0.66-0.8 for Open Addressing Hash Tables or 0.7 for classic Separate Chaining implementations.

But don’t get too excited; there are a few gotchas:

- To find an MPHF or PHF, we need to know all the keys in advance. After computing the PHF and building the Hash Table, we cannot add new entries; the data structure is read-only. To be 100% accurate, dynamic perfect hashing exists, but because it’s quite memory intensive, we rarely see it in practice.

- Computing an MPHF is not guaranteed to work all the time, at least not if we use an algorithm that takes (almost) linear or logarithmic time.

- The resulting Perfect Hash Function is complex and usually performs a secondary table lookup. In practice, it can be slower than a standard hash function.

The idea for generating PHFs and MPHFs is not new; it first appeared in 1984 in a paper called Storing a Sparse Table with O(1) Worst Case Access Time. A significant improvement was proposed in 2009 with the paper Hash, displace, and compress (which the current article is based upon).

Meanwhile, more algorithms have emerged, and most of them are already implemented and described in the cmph library. What is nice about cmph is that you can compile the lib as a standalone executable that allows you to generate MPHFs from the command line. Currently cmph supports the following algorithms: CHD, BDZ, BMZ, BRZ, CHM, FCH, CHM, and FCH, each with its own PROs and CONs, as explained on this page.

If you are passionate about this topic, you can also check Reini Urban’s Perfect-Hash for PHFs code generation, and his article on the topic.

In this article, we are going to implement in Java, a “naive” version of CHD, which is actually based on how Steve Hanov implemented it in python, in his article: “Throw away the keys: Easy, Minimal Perfect Hashing”, and this C implementation by William Ahern.

The code

If you want to checkout the code associated with this project:

git clone git@github.com:nomemory/mphmap.git

A glimpse

To get a better understanding of what we are going to achieve by the end of this article, let’s suppose we have a Set \(S\) of 15 Roman Emperors keys:

Set<String> emperors =

Set.of("Augustus", "Tiberius", "Caligula",

"Claudius", "Nero", "Vespasian",

"Titus", "Dominitian", "Nerva",

"Trajan", "Hadrian", "Antonious Pius",

"Marcus Aurelius", "Lucius Verus", "Commodus");

We want to find a function \(H\) that evenly distributes each of the keys to 15 hash buckets in the range [0,1, .. 14].

If we use Java’s built-in String.hashCode() on the keys, we will get a few collisions:

// Intiliaze buckets as an empty List<ArrayList<String>>

List<ArrayList<String>> buckets =

Stream.generate(() -> new ArrayList<String>()).limit(emperors.size()).toList();

// Distributing elements in the buckets

emperors.forEach(s -> {

// We apply & 0xfffffff, because, by default hashCode

// can return a negative value

int hash = (s.hashCode() & 0xfffffff) % buckets.size();

buckets.get(hash).add(s);

});

// Printing buckets contents

for (int i = 0; i < buckets.size(); i++) {

System.out.printf("bucket[%d]=%s\n", i, buckets.get(i));

}

Output:

bucket[0]=[Augustus]

bucket[1]=[]

bucket[2]=[Tiberius]

bucket[3]=[]

bucket[4]=[Lucius Verus]

bucket[5]=[]

bucket[6]=[]

bucket[7]=[]

bucket[8]=[Caligula]

bucket[9]=[Antonious Pius]

bucket[10]=[]

bucket[11]=[Dominitian]

bucket[12]=[Hadrian, Titus, Claudius]

bucket[13]=[Nerva, Marcus Aurelius]

bucket[14]=[Trajan, Vespasian, Commodus, Nero]

As you can see, the distribution is far from perfect; there are nine collisions in 15 buckets.

In this article, we will implement a class, PHF.java that will be able to evenly distribute the 15 Roman emperors into their own personal buckets. This would be the right thing to do because it would’ve been unfair to have "Trajan" sharing the same space with "Nero".

Set<String> emperors =

Set.of("Augustus", "Tiberius", "Caligula",

"Claudius", "Nero", "Vespasian",

"Titus", "Dominitian", "Nerva",

"Trajan", "Hadrian", "Antonious Pius",

"Marcus Aurelius", "Lucius Verus", "Commodus");

// Initializing our Minimal Perfect Hash Function we are going to build

// in this article

PHF phf = new PHF(1.0, 4, Integer.MAX_VALUE);

phf.build(emperors, String::getBytes);

// Puting elements in the buckets

final String[] buckets = new String[emperors.size()];

emperors.forEach(emperor -> buckets[phf.hash(emperor.getBytes())] = emperor);

// Printing the results

for (int i = 0; i < buckets.length; i++) {

System.out.printf("bucket[%d]=%s\n", i, buckets[i]);

}

Output:

bucket[0]=Titus

bucket[1]=Vespasian

bucket[2]=Claudius

bucket[3]=Marcus Aurelius

bucket[4]=Nero

bucket[5]=Nerva

bucket[6]=Caligula

bucket[7]=Commodus

bucket[8]=Augustus

bucket[9]=Tiberius

bucket[10]=Hadrian

bucket[11]=Lucius Verus

bucket[12]=Antonious Pius

bucket[13]=Trajan

bucket[14]=Dominitian

As you can see, there are no collisions now. Our function PHF.hash() works “flawlessly” in this regard: each Emperor to its own bucket.

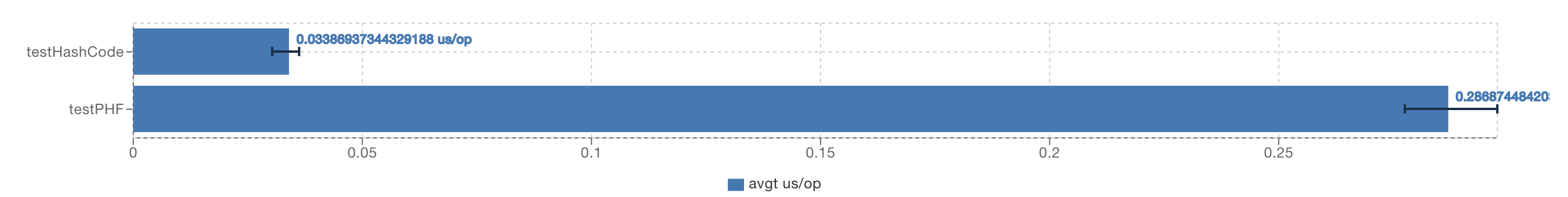

Don’t get too excited. Let’s “microbenchmark” how fast our new function is compared to the established Object.hashCode().

Being ten times slower than Object.hashCode() is not what I intended to show you, but you get the main idea, PHF.hash() will be slower. My implementation is not exactly the best, but even if you apply some heavy optimizations, you won’t be able to get significant improvements.

Now let’s see how PHF.java is implemented.

The algorithm in images

-

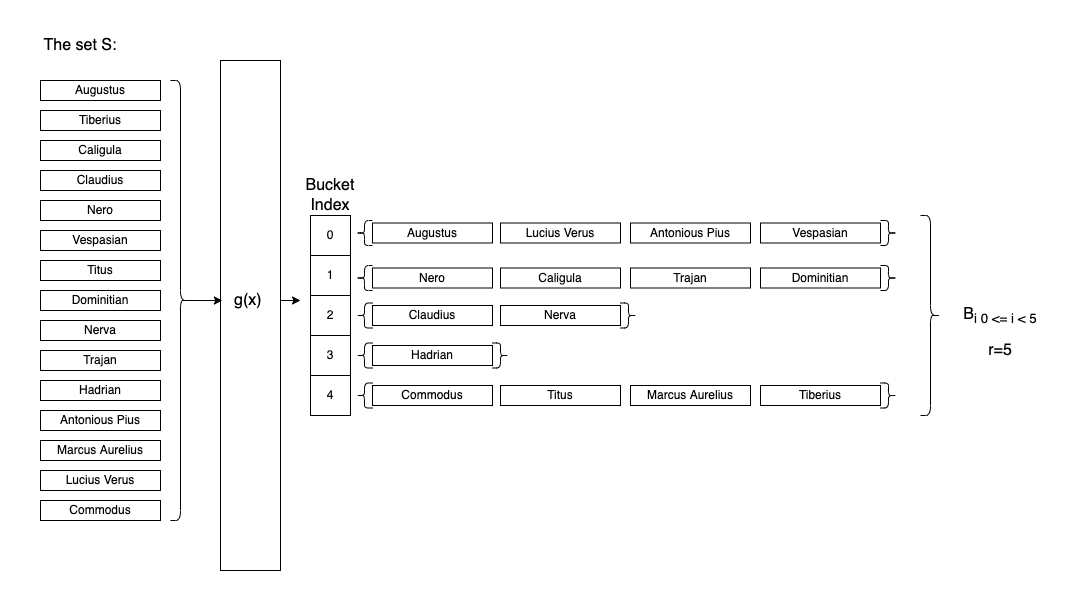

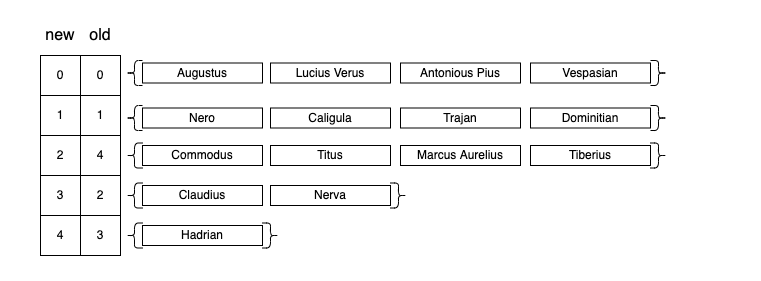

We split our initial \(S\), the set which contains all the possible keys, into virtual “buckets” \(B_{i}\) buckets of size \(0 \le i \lt r\). To obtain those buckets, we use a first-level hash function \(g(x)\), so that \(B=\{ x \mid g(x)=i \}\).

-

We sort the \(B_{i}\) buckets in descending order (according to their size, \(\mid B_{i} \mid\)), keeping their initial index for later use. The main idea is to start with the problematic buckets first (the ones having the most collisions).

! .

. -

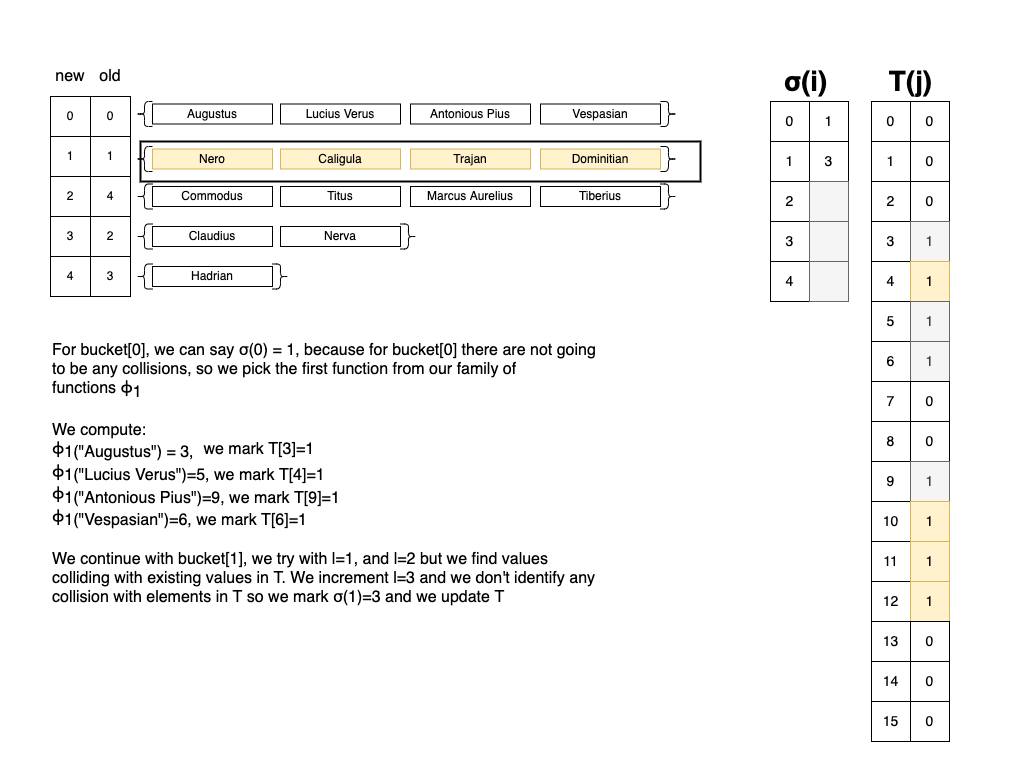

We initialize an array \(T=[0, 1, 2, ..., m-1]\) with

0elements. In our particular example,m=15. In \(T\) we keep track of elements for which our PHF don’t have collisions. -

We iterate over each bucket \(B_{i}\) with \(i\in\{0,1...,r-1\}\) in the order obtained at step

2., until \(\mid B_{i}\mid=1\) (the size of \(B_{i}\) is1)- For each element in \(B_{i}\), we compute \(K_{i} = \{ \phi_{l}(x) \mid x\in B_{i}\}\) and \(l\in[1,..]\), where \(\phi_{1}, \phi_{2}, \phi_{3}, ...\) is a family of hash functions, that or each \(l\) it returns a different value for \(\phi_{l}(x)\).

- We stop when \(\mid K_i \mid = \mid B_i \mid\) and \(K_i \cap \{j \mid T[j]=1\}=\emptyset\). This means that we found \(K_{i}\) elements for which there’s no previous collisions for the current \(l\).

- For \(j\in K_i\) we mark \(T[j]=1\)

- We store the value of \(\sigma(i)=l\) . At this point we know that the elements from \(B_{i}\) won’t colide if we apply \(\phi_l(x)\) on them. From a code perspective we can keep \(\sigma(i)\) in an array.

-

For the remaining buckets with \(\mid B_i \mid=1\), we will look into the remaining empty slots in \(T\), and one by one, we will put all remaining elements. We store \(\sigma(i)=-\text{position}-1\).

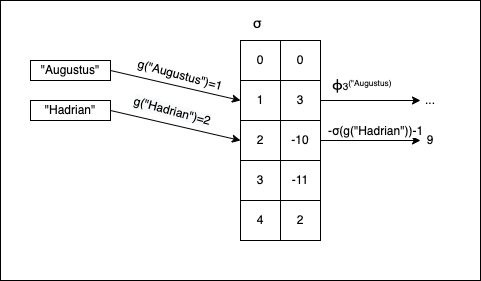

The last part is to find a way of computing \(H(x)\), which is our PHF: \(H(x) = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} \phi_{\sigma(g(x))}(x) & \mbox{if } \sigma(g(x)) > 0 \\ -σ(g(x))-1 & \mbox{if } \sigma(g(x))\leq 0 \end{array} \right.\)

Visually \(H(x)\) works like this:

Don’t worry if things don’t make a lot of sense now; the code is easier to implement than the actual presentation.

The implementation

The hash functions g(x) and \(\phi_l(x)\)

In practice we don’t need two separate functions for \(g(x)\) and \(\phi_l(x)\), we simply apply the following convention:

- We define \(g(x)=\phi_0(x)\) ;

- At step

4.1, when when we incremenent \(l\) for computing \(\phi_l(x)\) we start with \(l \in \{1,2,...\}\).

From a code perspective, my function of choice was MurmurHash, using this Apache implementation:

// Constants for 32-bit variant

private static final int C1_32 = 0xcc9e2d51;

private static final int C2_32 = 0x1b873593;

private static final int R1_32 = 15;

private static final int R2_32 = 13;

private static final int M_32 = 5;

private static final int N_32 = 0xe6546b64;

public static int hash32x86(final byte[] data, final int offset, final int length, final int seed) {

int hash = seed;

final int nblocks = length >> 2;

// body

for (int i = 0; i < nblocks; i++) {

final int index = offset + (i << 2);

final int k = getLittleEndianInt(data, index);

hash = mix32(k, hash);

}

// tail

final int index = offset + (nblocks << 2);

int k1 = 0;

switch (offset + length - index) {

case 3:

k1 ^= (data[index + 2] & 0xff) << 16;

case 2:

k1 ^= (data[index + 1] & 0xff) << 8;

case 1:

k1 ^= (data[index] & 0xff);

// mix functions

k1 *= C1_32;

k1 = Integer.rotateLeft(k1, R1_32);

k1 *= C2_32;

hash ^= k1;

}

hash ^= length;

return fmix32(hash);

}

private static int mix32(int k, int hash) {

k *= C1_32;

k = Integer.rotateLeft(k, R1_32);

k *= C2_32;

hash ^= k;

return Integer.rotateLeft(hash, R2_32) * M_32 + N_32;

}

private static int fmix32(int hash) {

hash ^= (hash >>> 16);

hash *= 0x85ebca6b;

hash ^= (hash >>> 13);

hash *= 0xc2b2ae35;

hash ^= (hash >>> 16);

return hash;

}

In this regard:

- \(g(x)\) is equivalent with

MurmurHash32.hash32x86(data, 0, data.length, 0) - \(\phi_l(x)\) is equivalent with

MurmurHash32.hash32x86(data, 0, data.length, l)

The PHF.java class

We start with the following constructor and class attributes:

protected double loadFactor;

protected int keysPerBucket;

protected int maxSeed;

protected int numBuckets;

public int[] seeds;

public PHF(double loadFactor, int keysPerBucket, int maxSeed) {

if (loadFactor>1.0) {

throw new IllegalArgumentException("Load factor should be <= 1.0");

}

this.loadFactor = loadFactor;

this.keysPerBucket = keysPerBucket;

this.maxSeed = maxSeed;

}

-

this.loadFactoris by default1.0if we want aMPHFor less than1.0if we want to generate aPHF. -

this.keysPerBucketrepresents the average keys per bucket \(B_{i}\) . For example if in \(S\) we have 15 elements, and we pickkeysPerBucket=3, then we will have 5 buckets: \(B_{0}, B_{1}, B_{2}, B_{3}, B_{4}\), each with an average of 3 elements. -

this.maxSeedis the maximum value of \(l\). If for example we cannot find \(K_{i}\) for \(l \lt \text{maxSeed}\), then we say our search for finding the MPHF failed and we throw an exception. -

this.seedscorresponds to \(\sigma(i)\) from the algorithm description.

The next step is to define two hash functions:

-

One for internal use (a wrapper) over

MurmurHash3.hash32x86(...); -

The actual \(H(x)\).

public int hash(byte[] obj) {

// g(x)

int seed = internalHash(obj, INIT_SEED) % seeds.length;

// if σ(g(x)) <= 0

if (seeds[seed]<=0) {

// we return -σ(g(x))-1

return -seeds[seed]-1;

}

// we return ϕ_σ(g(x))(x)

int finalHash = internalHash(obj, seeds[seed]) % this.numBuckets;

return finalHash;

}

// IF val == 0 => g(x)

// ELSE acts like ϕ(x)

protected static int internalHash(byte[] obj, int val) {

return MurmurHash3.hash32x86(obj, 0, obj.length, val) & SIGN_MASK;

}

At this point, we introduce a class called: PHFBucket. The sole purpose of this class, is to store the original index of the bucket after step 2.:

private static class PHFBucket implements Comparable<PHFBucket> {

ArrayList<byte[]> elements;

int originalBucketIndex; // stores the original index

static PHFBucket from(ArrayList<byte[]> bucket, int originalIndex) {

PHFBucket result = new PHFBucket();

result.elements = bucket;

result.originalBucketIndex = originalIndex;

return result;

}

// Written in a way so we can sort in reverse order

@Override

public int compareTo(PHFBucket o) {

return o.elements.size() - this.elements.size();

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Bucket{" +

"elements.size=" + elements.size() +

", originalBucketIndex=" + originalBucketIndex +

'}';

}

}

The last step is to define the actual algorithm. At the end, this.seeds[] will contain all the values necesarry to compute the MPHF (or PHF).

public <T> void build(Set<T> inputElements, Function<T, byte[]> objToByteArrayMapper) {

int seedsLength = inputElements.size() / keysPerBucket; // m

int numBuckets = (int) (inputElements.size() / loadFactor); // r

this.numBuckets = numBuckets;

// The seeds have to be calculated

// From an algorithm perspective this is σ(i)

this.seeds = new int[seedsLength];

// Fill the buckets with empty values initially

ArrayList<byte[]> buckets[] = new ArrayList[seedsLength];

for (int i = 0; i < buckets.length; i++) {

buckets[i] = new ArrayList<>();

}

// Adding elements to buckets

// (step 1. from the algorithm)

inputElements.stream().map(objToByteArrayMapper).forEach(el -> {

int index = (internalHash(el, INIT_SEED) % seedsLength);

buckets[index].add(el);

});

// Sorting so we can start with buckets with the most items

// (step 2. from the algorithm)

ArrayList<PHFBucket> sortedBuckets = new ArrayList<>();

for (int i = 0; i < buckets.length; i++) {

sortedBuckets.add(PHFBucket.from(buckets[i], i));

}

sort(sortedBuckets);

// For each bucket we try to find a function for which the seed has no collisions

// occupied represents T

// (step3)

BitSet occupied = new BitSet(numBuckets);

int sortedBucketIdx = 0;

PHFBucket bucket;

Integer originalIndex;

ArrayList<byte[]> bucketElements;

Set<Integer> occupiedBucket;

// (step 4.)

for(; sortedBucketIdx < sortedBuckets.size(); sortedBucketIdx++) {

bucket = sortedBuckets.get(sortedBucketIdx);

originalIndex = bucket.originalBucketIndex;

bucketElements = bucket.elements;

// If the buckets start to have a single element we don't have

// to do any additional computation, we can break the loop

if (bucketElements.size()==1) {

break;

}

// For each seed

int seedTry = INIT_SEED + 1;

for (; seedTry < maxSeed; seedTry++) {

occupiedBucket = new HashSet<>();

// For each element in the bucket

int eIdx = 0;

for (; eIdx < bucketElements.size(); eIdx++) {

int hash = internalHash(bucketElements.get(eIdx), seedTry) % numBuckets;

if (occupied.get(hash) || occupiedBucket.contains(hash)) {

// Trying with this seed is not successful, we break the loop

// So we can try with another seed

break;

}

occupiedBucket.add(hash);

}

if (eIdx == bucketElements.size()) {

// In thise case elements per bucket displace well,

// we can add them to occupied and the seed to 'seeds'

occupiedBucket.forEach(occupied::set);

this.seeds[originalIndex] = seedTry;

break;

}

}

// If the seed == SEED_MAX then we've failed constructing a Perfect Hash Function

// This means we've exhausted the possible seeds

if (seedTry==maxSeed) {

throw new IllegalStateException("Cannot construct perfect hash function");

}

}

// At this point only the buckets with one element remain, we need to add them

// to seed, we continue the iteration

// (step 5.)

int occupiedIdx = 0; // start from the first position

for(; sortedBucketIdx < sortedBuckets.size(); sortedBucketIdx++) {

bucket = sortedBuckets.get(sortedBucketIdx);

originalIndex = bucket.originalBucketIndex;

bucketElements = bucket.elements;

if (bucketElements.size()==0) {

break;

}

while(occupied.get(occupiedIdx)) {

// increase position so we can find an empty slot

occupiedIdx++;

}

occupied.set(occupiedIdx);

// We subtract (-1) to cover 0 cases

this.seeds[originalIndex] = -(occupiedIdx)-1;

}

}

Bonus: Creating a read-only Map<K,V>

Now that we have PHF.java, we can create a Hash Table calledReadOnlyMap<K,V>, that only allows read operations:

public class ReadOnlyMap<K,V> {

protected static final double LOAD_FACTOR = 1.0;

protected static final int KEYS_PER_BUCKET = 1;

protected static final int MAX_SEED = Integer.MAX_VALUE;

private PHF phf;

private ArrayList<V> values;

private Function<K,byte[]> mapper;

public static final <K,V> ReadOnlyMap<K,V> snapshot(Map<K, V> map, Function<K, byte[]> mapper, double loadFactor, int keysPerBucket, int maxSeed) {

ReadOnlyMap<K,V> result = new ReadOnlyMap<>();

result.phf = new PHF(loadFactor, keysPerBucket, maxSeed);

result.phf.build(map.keySet(), mapper);

result.values = new ArrayList<>(map.keySet().size());

for (int i = 0; i < map.keySet().size(); i++) {

result.values.add(null);

}

result.mapper = mapper;

map.forEach((k, v) -> {

int hash = result.phf.hash(mapper.apply(k));

result.values.set(hash, v);

});

return result;

}

public static final <K,V> ReadOnlyMap<K,V> snapshot(Map<K,V> map, Function<K, byte[]> mapper) {

return snapshot(map, mapper, LOAD_FACTOR, KEYS_PER_BUCKET, MAX_SEED);

}

public static final <V> ReadOnlyMap<String, V> snapshot(Map<String, V> map) {

return snapshot(map, String::getBytes);

}

public V get(K key) {

int hash = phf.hash(mapper.apply(key));

return values.get(hash);

}

}

Using the ReadOnlyMap<K,V> is quite straightforward. We only have one method to create a ReadOnlyMap<K,V> as a snapshot from a “normal” read-write Map<K,V>:

public static void main(String[] args) {

Set<String> emperors =

Set.of("Augustus", "Tiberius", "Caligula",

"Claudius", "Nero", "Vespasian",

"Titus", "Dominitian", "Nerva",

"Trajan", "Hadrian", "Antonious Pius",

"Marcus Aurelius", "Lucius Verus", "Commodus");

// Creates a "normal map" from the given keys

final Map<String, String> mp = new HashMap<>();

emperors.forEach(emp -> {

mp.put(emp, emp+"123");

});

// Creates a "read-only map" from the previous map

final ReadOnlyMap<String, String> romp = ReadOnlyMap.snapshot(mp);

emperors.forEach(emp -> {

System.out.println(emp + ":" + romp.get(emp));

});

}

Bonus section: Benchmarking HashMap<K,V> vs. ReadOnlyMap<K,V>

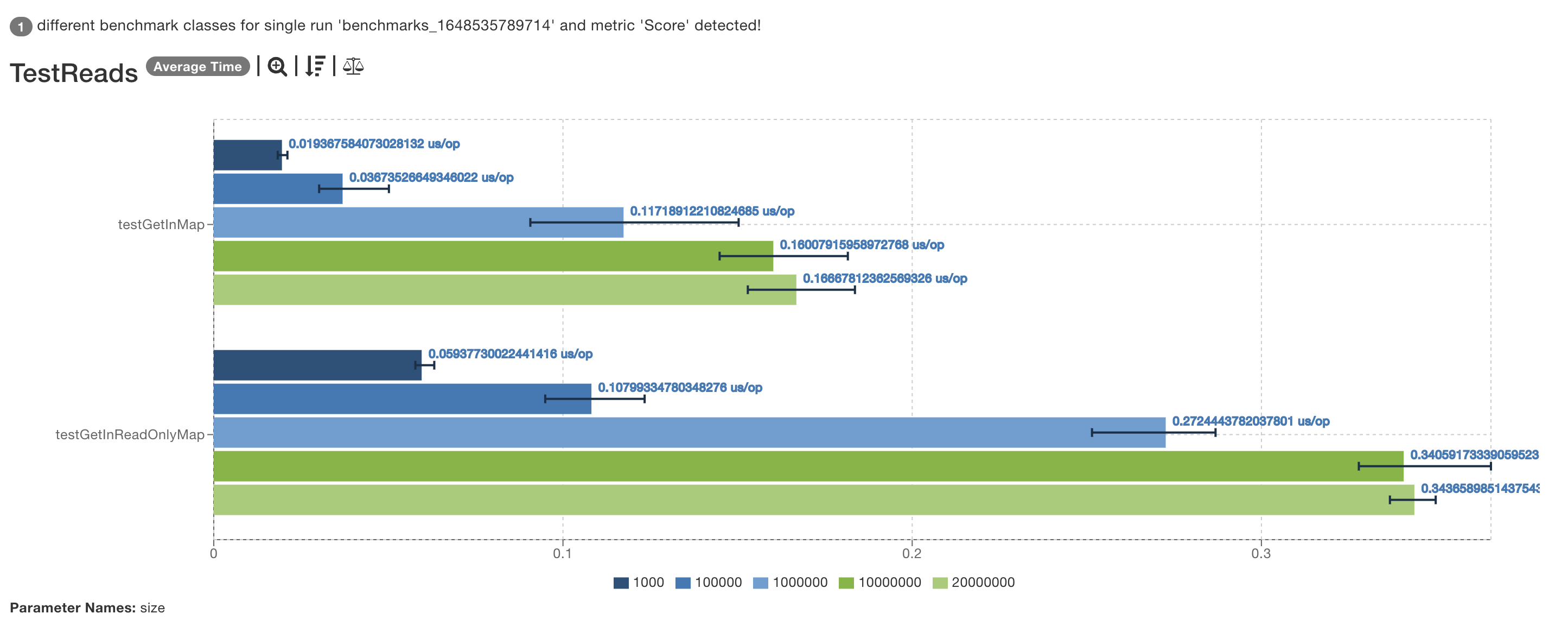

We’ve already benchmarked how “fast” is PHF.hash() in the beggining in the article, and we’ve seen things can be up to 10 times slower than Object.hashCode(). But let’s see how fast is ReadOnlyMap<K,V> vs HashMap<K,V>.

In this regard I’ve written the following benchmark, the tests the performance of the get operation on a Maps of 20_000_000 keys:

@BenchmarkMode(Mode.AverageTime)

@OutputTimeUnit(TimeUnit.MICROSECONDS)

@State(Scope.Benchmark)

@Fork(value = 3, jvmArgs = {"-Xms6G", "-Xmx16G"})

@Warmup(iterations = 3, time = 10)

@Measurement(iterations = 5, time = 10)

public class TestReads {

@Param({"1000", "100000", "1000000", "10000000", "20000000"})

private int size;

private Map<String, String> map;

private ReadOnlyMap<String, String> readOnlyMap;

private MockUnitString stringsGenerator = words().map(s -> s + ints().get()).mapToString();

private List<String> keys;

@Setup(Level.Trial)

public void initMaps() {

keys = stringsGenerator.list(size).get();

this.map = new HashMap<>();

keys.forEach(key -> map.put(key, "abc"));

this.readOnlyMap = ReadOnlyMap.snapshot(map);

}

@Benchmark

public void testGetInMap(Blackhole bh) {

bh.consume(map.get(From.from(keys).get()));

}

@Benchmark

public void testGetInReadOnlyMap(Blackhole bh) {

bh.consume(readOnlyMap.get(From.from(keys).get()));

}

}

The results were quite interesting:

Even if the hash function is slower, given the higher memory locality, ReadOnlyMap performs a little bit faster, than a normal HashMap<K,V>.

Later Edit:

The initial benchmark performed was incorrect, so I’ve reported erroneous results: the reality is that HashMap<K,V> faster.

Comments