I’ve promised myself never to use gradle

The current article won’t be an exhaustive technical analysis on Gradle but more like a spontaneous rant.

Firstly, the time I am willing to allocate for learning a build tool will always be limited. Secondly, I try to be fair, so the list of things I expect from a build tool is small:

- Let me list a few dependencies by using a purely descriptive approach;

- Please give me a stable (!) interface to write plugins for “extravagant” features. If other devs are building open-source plugins, I am willing to use them instead of writing them independently.

- After the initial effort to write the build file, I should rarely touch it (unless I am incrementing version numbers).

Jokes “inside”, I’ve just described Maven.

Unfortunately, Gradle lost its way between the upgrade from version 4.x to 5.x, or between the upgrade from version 5.x to 6.x, or between the upgrade from version 6.x to 7.x, or between 7.x to 8.x. Or maybe Gradle was never the way. We were momentarily happy not having to write and read (pom.)XML files ever again, and we jumped the boat too early. Our problem was never Maven, but XML…

Gradle and the cognitive load

The moment you exit the realm of straightforward build files, you will become lost and incredibly lonely. This will happen because you never had the patience (by then!) to read the documentation in its entirety. And bare in mind, Gradle’s documentation is not something you can skim on the weekend or from your mobile phone while sitting on the bus. On the contrary, it’s a “hard” read, full of specific technical jargon you need to familiarize yourself with.

So let me give you an example, the chapter “Learning the Basics -> Understanding the Build Lifecycle”, starts with the following paragraph. This should be an easy read, given it’s an introductory article:

Quickly, without opening your CS reference book, tell me what’s a Directed Acyclic Graph. It’s ok; you don’t have to open your CS reference book because the authors of the documentation were kind enough to link a Wikipedia article:

After digging up the documentation for a few days (or up to a week, if you want to understand how Multi-Project builds work), things will become much clearer as you’ll experience a few Eureka moments. This period is critical. After this week, you will either hate or love Gradle. It only depends on your overall tolerance to the complexity and over-engineered solutions.

In any case, kudos!; you are now part of a select group of people who managed to go through the Gradle documentation. But, it will be wise to hide this fact from your team. Otherwise, your colleagues will make you the guy responsible for the build file. This is a cross responsibility not always worth carrying.

My advice:

- Gradle is not the tool you hack your way into by copying paste stuff from StackOverflow. If you haven’t done so already, allocate time to read the documentation.

The disregard for backward compatibility

Java prides itself on being a conservative technology (in the lack of better wording). The standard API rarely changes, and the old stuff keeps working, even if it falls from grace. People are not using Vector<T> anymore, but this doesn’t mean Vector<T> was removed from the Standard Library. To a lesser extent, the ecosystem of libraries, frameworks, and tools surrounding and supporting Java inherits this approach. Developers make great efforts to maintain backward compatibility, even between major versions.

This is not the case with gradle. Incrementing to a new major version is always painful (for non-trivial builds):

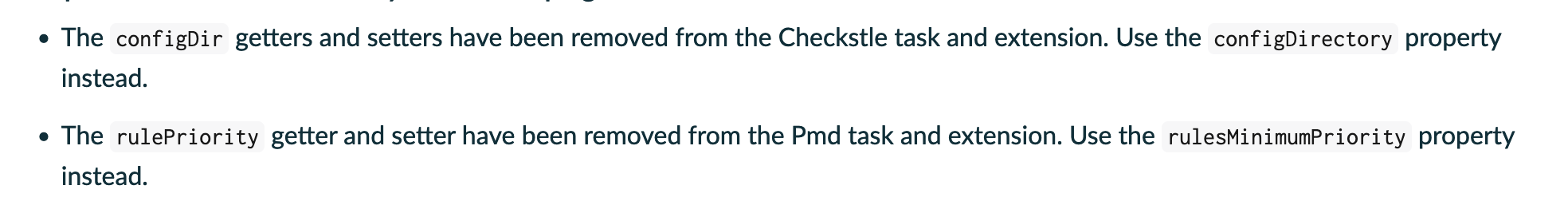

- The API always change. Sometimes for cosmetical reasons:

- Or subtle changes that can affect existing behavior:

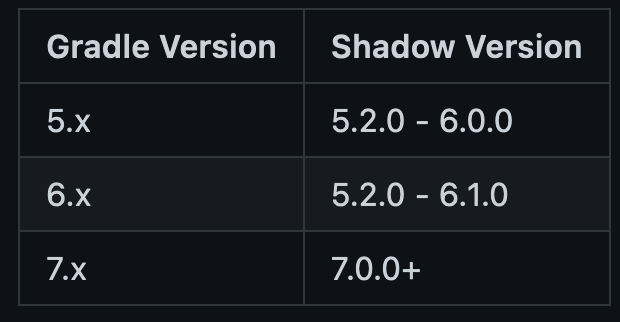

Because of the API changes, 3rd party plugins you depended upon won’t work anymore unless the original authors are updating them. For this reason, the very popular plugin Gradle Shadow comes into 3 “flavors”, for each API change major Gradle version:

Maintaining multiple versions puts an unnecessary burden on the open-source maintainer. For example, the famous Log4shell exploit was never fixed in older versions of the Gradle Shadow plugin (see issue), forcing users to upgrade either update the Gradle Version, and by this provoking even more backward compatibility havoc, or implementing alternative solutions.

On the one hand, I love that the Gradle people are forward-thinking, but the way things change from version to version is sometimes too much. If you plan to use Gradle, you should permanently update it. If you get to the point of being a few (major) versions behind, you will make your life harder than it should.

My advice:

- Migrating to a major Gradle version can be a hurdle, so allocate time wisely from a project perspective. Read the changelog with great attention;

- Limit your usage of 3rd party Gradle plugins.

- Prefer to write your plugins if possible.

Gatekeeping the Pandora’s Box

Please make no mistake; when you choose to use Gradle, you will program your build file, not configure it.

The build.gradle is a running program in disguise (DSL). This means you can write (business) logic into a build file by creating your functions and hooking them into the Directed Acyclic Graph we were previously speaking of. So even if it’s not explicitly required, it’s time for you to learn a little bit of groovy or kotlin, depending on the Gradle dialect you pick.

As a fun exercise, let’s write a build.gradle file that fails the build if the weather temperature in Bucharest is lower than 25 degrees (Celsius). We need to write a new task called howIsTheWeatherInBucharest, connect to the https://openweathermap.org/ API through a REST call, perform the check and fail the build if the day is too cold for programming.

// rest of the build file

task howIsTheWeatherInBucharest {

doLast {

// Quick and dirty code

def apiKey = '<...enter api code here...>'

def req = new URL('https://api.openweathermap.org/data/2.5/weather?q=Bucharest&units=metric&appid=' + apiKey).openConnection()

req.setRequestMethod("GET")

req.setRequestProperty("Content-Type", "application/json; charset=UTF-8")

req.setDoOutput(true)

def is = req.getInputStream();

def resp = new Scanner(is).useDelimiter("\\A").next();

def json = new groovy.json.JsonSlurper().parseText(resp)

def temp = Double.parseDouble(json.main.temp.toString())

if (temp < 25.0) {

throw new GradleException("Build file, the weather in Bucharest is bad")

}

}

}

compileJava.dependsOn(howIsTheWeatherInBucharest)

Having the ability to write code is seductive, but it opens Pandora’s Box. The programmer’s reflex to throw in some custom functions to make things work will kick in, especially if the build file is complex. And to be honest, writing your build file with a programmer’s mindset is more natural than trying to circumvent the DS.

But let’s take a step back, and ask ourselves if this is what we want from a build tool?! Writing quick and dirty code can spiral into writing more and more quick ‘n dirty code. Other people in your extended team can add their personal quick ‘n dirty code. Without the ability to properly debug the build process and the non-standard hacks people are willing to put in the build file, things can become less portable and extremely environment-dependent or simply not idempotent. Should you always be online to build your project? Should you be inside a Private Network?

Do you remember when people were creating .sh scripts to build things? There’s a reason we’ve stopped doing so.

Even if it’s easy to do so, the Gradle build shouldn’t replace a proper CI/CD pipeline, but I’ve worked and seen projects where the build process was doing much more than assembling a fat jar. It ran tests and integrated directly with Sonarqube, created custom reports based on the static code analysis results, performed infrastructure changes, etc. Why!? Because it was possible.

My advice:

- Keep your build file as declarative as possible and stick to the DSL.

- Avoid adding arbitrary logic even if it’s fast and it works!;

- Don’t add tasks in your build file that can be implemented as individual steps in a proper CI/CD pipeline;

- If you understand how Gradle works try to gatekeep the file and review whatever changes your colleagues make.

Groovy, Kotlin, do you speak it ?!

Gradle 5.0 came with a “game”-breaking change: devs were allowed to use an experimental Kotlin DSL to replace the historical groovy DSL. In theory, this was terrific news, especially for the Android folks who were already flocking to Kotlin. The reality, this fragmented the community and brought even more confusion to the uninitiated.

For example, searching Stackoverflow for Gradle issues suddenly became more arduous. First of all, the answers you will find on the Internet are most of the time outdated. You cannot simply hack your way with a solution targeting 5.0 if you are already at version 7.0. Chances are it won’t work. But now you also need to be attentive to the dialect! You can find a working solution that uses Groovy, and you will have to translate it yourself (manually) to Kotlin.

Compared to the Groovy DSL, the Kotlin DSL seems to be more strict and more opinionated. After all, Kotlin has a stricter type system compared to groovy. So if you are a Java developer planning to use Gradle with the Kotlin DSL, you have to be familiar with Groovy (to be able to read the old materials), but you also need to learn enough Kotlin to be able to write your build file. A little bit of learning new things didn’t kill anyone, but I am asking again: Why is it necessary to learn a new programming language to master a build tool!?

My advice:

- I still use the groovy dialect simply because there are more materials to get inspiration from. It’s 2022, and things might change in the future;

Abrupt final thoughts

I’ve promised myself not to use Gradle anymore, but I still do it from time to time, especially for smaller, contained, personal projects.

Comments